When a Generation Disagrees With Itself

Economic precarity and digital politics have forged a new kind of divide — one that isn’t between generations, but within them

As 2025 unfolds, one of the most persistent illusions in political commentary continues to collapse , the idea that Generation Z, often framed as a singular, progressive wave sweeping across the democratic world, is moving in ideological unison. That story, never entirely accurate, now reads like fantasy. In its place, we’re left with a much messier — and far more revealing — reality: a generation not just divided, but diverging, with the most defining fault line no longer class, education, or geography, but gender.

This isn’t some quirky electoral footnote buried in a mid-cycle polling memo. It has become a defining axis of modern politics, consistent across borders, measurable across elections, and intensifying rather than fading. In country after country, young men and young women are not merely drifting apart politically; they are building entirely separate political realities. They watch different videos, share different grievances, believe in different futures, and vote — increasingly and decisively — for opposing visions of the world.

South Korea: Where the Gender War Is Electoral

Few places make the division more legible than South Korea, where the April 2024 general election turned gender into open political warfare. According to Gallup Korea, men in their twenties backed conservative parties at rates above 40%, with some polling even higher among those who supported abolishing the Gender Equality Ministry, a key symbolic institution. Women in the same age bracket, by contrast, voted overwhelmingly for progressive parties, not out of broad ideological loyalty, but in direct response to what they viewed as an explicit assault on their rights, dignity, and presence in public life. The resulting 30-point gap wasn’t a statistical fluke; it was a statement of separation.

And the divide didn’t end with the election. Throughout 2025, in local races and national discourse, that gender split has continued to shape debate, not simply over what kind of government South Koreans want, but over whose struggles should even be considered legitimate.

Germany: A Split Generation, Two Political Directions

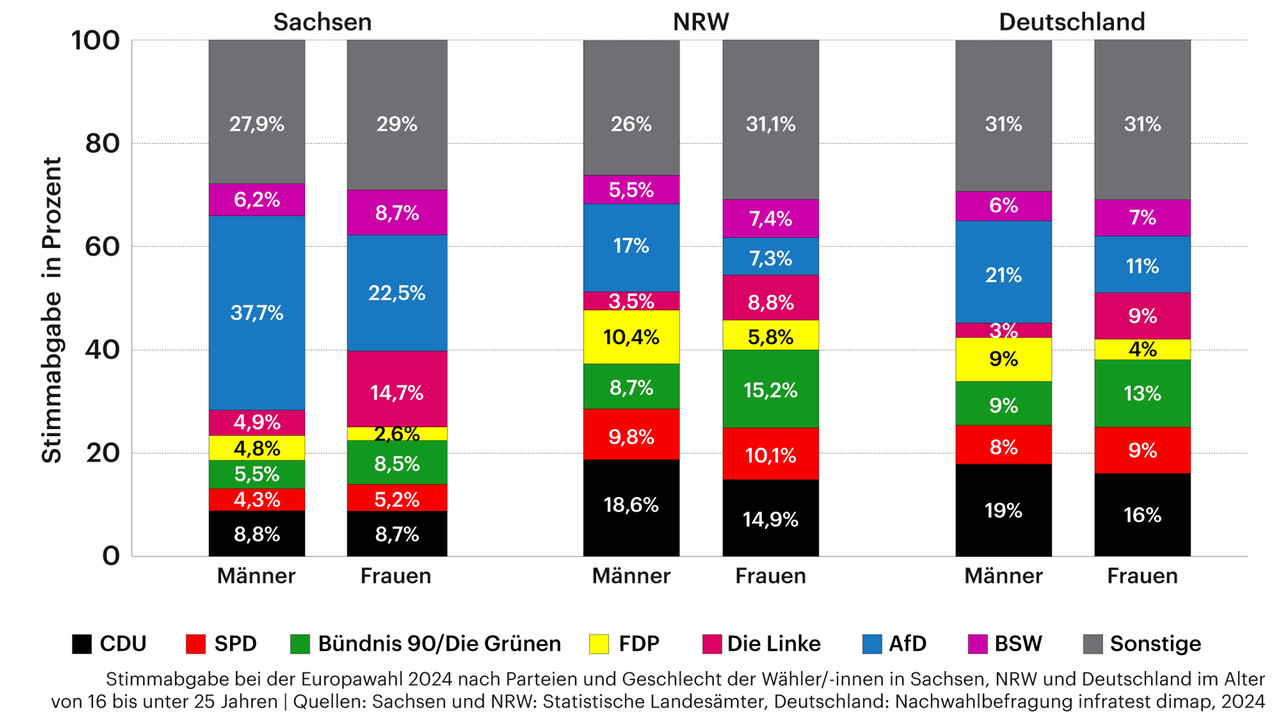

In Germany, the pattern has been less explosive but no less pronounced. During the 2024 European Parliament elections, 22% of men under 24 voted for the far-right Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), a party whose rejection of immigration, climate action, and what it calls “gender ideology” seems to strike a chord with a younger male audience feeling increasingly sidelined in political narratives. Among women in the same cohort, AfD support barely registered. Instead, they turned toward Die Linke and the Greens, parties not only offering leftist economic platforms, but addressing reproductive rights, gender equity, and the climate crisis as central, not peripheral, to national identity.

What’s emerging in Germany is not merely a disagreement about policy; it is, increasingly, a disagreement about the basic purpose of politics, whether it exists to restore a sense of lost normalcy or to dismantle structures that were never equitable to begin with.

The United States: A Generation Pulling Itself Apart

If there was any lingering doubt that the gender split among Gen Z is structural rather than situational, the 2024 U.S. presidential election erased it. The final tallies showed Kamala Harris winning 61% of women under 30, while Donald Trump secured 48% of men in the same group, a 17-point gender gap that stands as the largest in recorded U.S. electoral history for voters that young. This wasn’t a matter of turnout or a last-minute messaging mismatch. It was a reflection of two highly engaged, highly opinionated electorates who no longer interpret reality through the same lens.

In the months since, the split has not only held but deepened. A May 2025 Pew Research study found that while 71% of Gen Z women report engaging with political content online on a weekly basis, just 47% of Gen Z men do the same — and what they consume, when they do engage, bears almost no resemblance. Young men are more likely to find themselves in algorithmic tunnels of economic grievance and anti-woke backlash, while young women are organizing around climate, healthcare, reproductive rights, and labor justice. These are not two sides of a shared debate. They are two parallel political cultures, increasingly self-contained and self-reinforcing.

Two Sets of Conclusions From the Same Conditions

The instinct, particularly among older political analysts, has been to assume that a shared generational experience — economic precarity, housing shortages, climate anxiety — will naturally lead to a shared political agenda. But Gen Z is now making it abundantly clear that this assumption no longer holds. Faced with similar structural pressures, men and women are interpreting their conditions differently, responding with different emotional registers, and arriving at very different political conclusions.

For many young men, especially those watching the economic ladder grow ever steeper and less secure, there is a growing sense of being excluded, not just from opportunity, but from the national narrative about who deserves attention, sympathy, or structural support. In this context, the language of grievance offered by right-wing influencers and political figures doesn’t just appeal — it explains. It reframes frustration as justified anger and presents liberalism not as progress but as provocation. The message is clear: you were promised more than this, and someone else took it.

Young women, navigating many of the same economic conditions but layered with persistent threats to bodily autonomy, gender-based violence, and structural underrepresentation, are interpreting the moment very differently. For them, this is not a story of recent loss, but of long-standing exclusion, and their political impulse is not restoration but transformation. They are not seeking to reclaim power they feel entitled to; they are seeking to claim power they have never fully had.

Digital Infrastructure Is Cementing the Divide

If gender-based political divergence was once a matter of social context or family background, it’s now being industrially reinforced by digital design. The social media platforms where Gen Z spends an inordinate amount of its political life do not reward shared conversation, they reward affirmation and acceleration. TikTok’s algorithm, for instance, doesn’t just show users what’s trending; it feeds them what is already emotionally legible. A young man scrolling videos about rent inflation is quickly served libertarian takes on personal freedom and broken institutions. A young woman watching similar content is directed toward tenant union organizing and critiques of late-stage capitalism. The divergence is not incidental. It is engineered.

And so, by the time the two meet in a university lecture hall or workplace Slack, they are not disagreeing over details. They are disagreeing over what the fight is even about.

The Strategic Implications — and the Democratic Cost

Political strategists in 2025 have largely stopped trying to unify Gen Z. The gender divide has proven durable enough that campaigns now plan around it, with separate influencers, issues, and message tracks for men and women under 30. The idea of a cohesive “youth vote” has been functionally retired; it survives mostly as a myth in polling crosstabs.

For democracy, the consequences are harder to chart. A generation unable to find internal consensus, even in moments of shared instability, may struggle to exert meaningful pressure on the systems it’s poised to inherit. But this also shatters the illusion of Gen Z as a uniform bloc of digital natives and progressive idealists. What we’re seeing instead is a generation fractured not by apathy, but by belief — fiercely held, and increasingly incompatible.

Not a Lost Generation — a Split One

What’s become clear is that political identity can no longer be cleanly sorted by age. Gen Z, shaped by the same crises but arriving at different conclusions about what those crises demand, has produced not a shared movement but dueling ones. They are not united, and they are not confused, they are deliberate, divergent, and in many cases, disinterested in reconciliation.

That doesn’t mean they lack political power. It means that power, like the generation itself, will be harder to predict — and harder to organize — than anyone expected.

I had written a personal outro — just a few thoughts about why the centre-left keeps losing ground, why being online too much makes everything feel more extreme than it is, why men and women are radicalizing in opposite directions, and why language has become this strange test you have to pass to be taken seriously.

It turned into a longer draft, not a bad one, but as I reread it, I started to hear the very tone I was trying to avoid. It wasn’t meant to be condescending, but it started to sound like it anyway: too explained, too careful, trying too hard to land clean.

So I scrapped most of it. And kept the one line that still feels right:

Maybe — like one hell of a song says — we meet halfway. Not because it fixes anything, but because standing on opposite ends of the room shouting is just getting old.

Okay. If you’ve made it this far… thank you. Until next time, take care.

Alba